BERLIN ART LINK STUDIO VISIT

Article by Adela Yawitz, BERLINARTLINK, September 2012

Michael Luther’s studio in Friedrichshain is full. His paintings cover every available white surface from floor to ceiling, and additional, large paintings too big to be hung are stacked against one of the walls, their colorful edges peeking. For each painting he has made recently, he’s also saved his color palette, so that each work is doubled with an abstract color chart of its components. Saving the evidence of his painting activity is important, since his ongoing subject, across a range of applications, always circles around the process of painting itself, its materials, its goals, and the meditative time spent alone with the canvas.

It is fitting, then, that the only space the artist keeps clear of finished works is where he is working on his current paintings. This area is kept separate from any distracting clutter or former ideas, which is crucial to his meditative and solitary process. As he offers me fresh coffee and croissants, and talks about his favorite music, I see that there’s no separation between Michael Luther’s living and his work space. He is constantly surrounded by his images, in a way he says makes him see the slightest imperfections, while they are in progress, until they slowly become an invisible part of his everyday environment.

Luther’s work was featured in this week’s BERLINER LISTE art fair as part of the 2012 Berlin Art Week. His monumental landscape painting “Colourado” (2005) was displayed in the fair’s main space and additional works were shown in a separate individual booth featuring a sampling of paintings various past series.

As we walk around the studio, it becomes clear that Luther works horizontally, developing parallel lines of thought and work in different projects, but letting them all coexist in the studio. The simultaneous development of his series is at times practical: “Colourado”, for instance, took six months and a total of 1500 hours to complete, and other ideas, such as his color field experiments, had to be explored simultaneously. He also embraces this distributed practice as a principle: he insists that his different projects, which can seem visually unrelated, all revolve around the same core subjects and share the same motivation.

As he works on them in parallel, ideas come up that contribute to another series, or start an idea for a new project. The core question he engages in all of his series is, as he says with a smile, “what is it all about”; in other words, what can be done, as a painter ? and quite physically, with the paint ? and then trying to find some new way out of that historical endpoint. Finishing one series, and moving along systematically, would be artificial, and might imply that his question was in some way solved, whereas he thinks of it as an ever-challenging pursuit, which can be humorous, grave, circular, unsolvable.

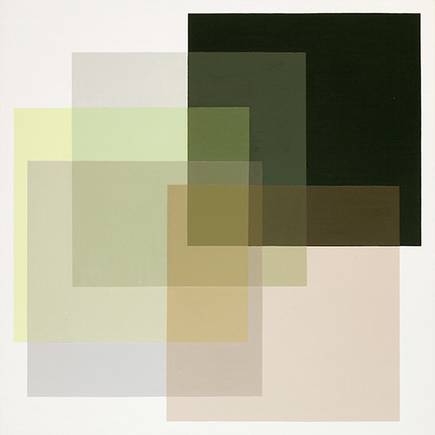

Luther’s current series of color fields and “screens” demonstrates his meditative mode of work, and its incongruous visual effect. He produces a photoshop color scheme, which is then meticulously, “photo realistically” reproduced and applied to the canvas in careful geometrical lines. The labor, concentration and technique invested in the work replace its image as the “subject” of the piece: since the random color scheme already existed digitally, its importance becomes why and how the artist recreated it manually. The computer-generated colors are unnaturally hard to match with physical paint, even though our eyes can easily detect when even one color is wrong. He rebuilds the computer’s graphic breakdown of color back into material color, and invests it with his own labor and time.

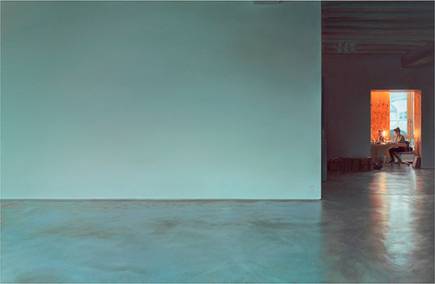

In other series, Luther addresses painting’s space and the painter’s work more literally, as it comes in contact with the institutional art world. In these pieces, the main spaces are left empty, and any paintings are turned to the wall; despite their realism, their main expanses are abstract whites and pale grey-blues. Even in his realistic view of the business side of art, he leaves the wall blank, still demanding the question of what it all might be about.

The question continues to challenge him, unrelentlessly, through his new and old work, and even as his studio holds all his previous answers, he continues to meditate on, and constantly produce, new possible meanings.